Child Development Theories: A Journey Through Time, Society, and Connection

- The Four-Pronged Approach to Human Development

- Stages, Conflicts, and Virtues

- Child Development Evolution timeline

- Generation Overview, Impact and Mental Health

- The Role of AAC in Supporting Child Development

- Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: Facilitating Self-Actualisation

- Chemical Exposure and Sustainability

- Call to Action

The evolution of child development theories is deeply connected to broader historical, biological, and technological changes that have shaped human societies.

The growing recognition of neurodiversity necessitates an ongoing reimagining of how we parent, teach, and learn. These changes highlight the importance of tools for connection, such as AAC (Augmentative and Alternative Communication), that facilitate and support children’s unique needs, helping them navigate and find meaning in a world that often requires adaptation.

From the early philosophical insights into childhood, through the scientific revolutions in biology and psychology, to the rise of inclusive educational practices and digital learning tools, our understanding of how children grow and develop has become more nuanced and interconnected. AAC, along with the many other frameworks that exist today, will continue to play a critical role in shaping a future where every child’s voice is heard, valued, and respected.

In a society that constantly evolves and challenges traditional norms, it’s critical to appreciate that each child’s developmental journey is unique—with tools like AAC, emotional intelligence, and inclusive education as vital support systems.

The Four-Pronged Approach to Human Development

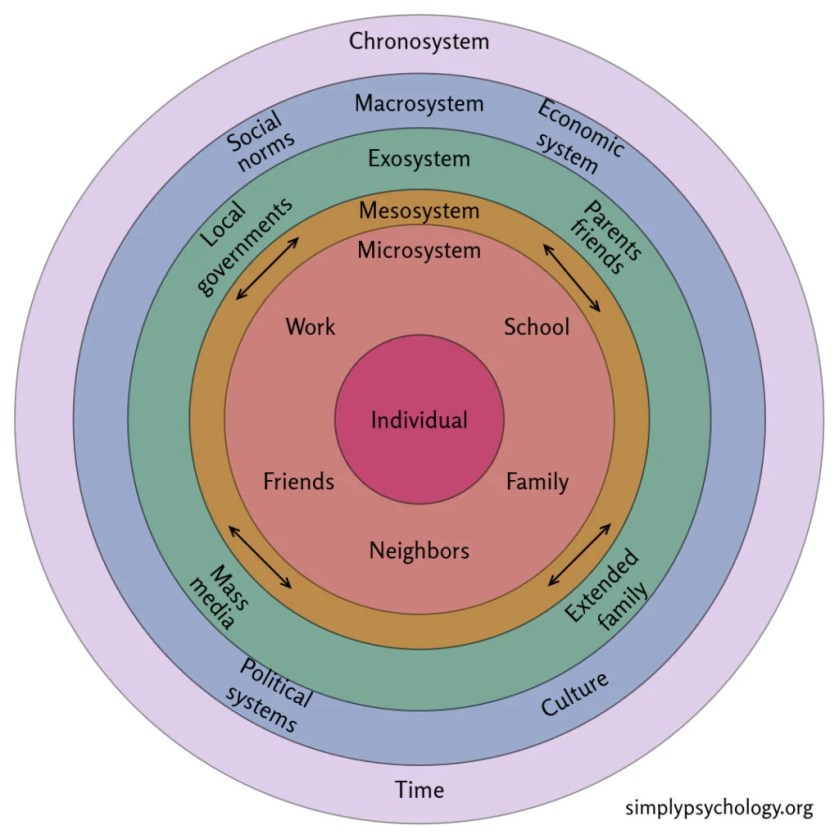

A great way to deepen our understanding of these interconnected factors is by exploring Urie Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory, which outlines how children’s development is shaped by their interactions with different layers of their environment, from immediate family settings (the microsystem) to broader societal and cultural factors (the macrosystem).

A Bio-Psycho-Social-Societal Lens: Understanding the Whole Child

Biological: This focuses on physical growth, brain development, and genetics—basically, the body’s role in development.

Psychological: This covers emotional and cognitive development, how children form identities, and their inner world.

Social: This looks at the immediate environment—family, peers, and community—and how these relationships shape children’s behaviour and skills.

Societal: This examines the broader societal forces—like government policies, education systems, media, and cultural expectations—that influence a child’s opportunities and sense of self.

Stages, Conflicts, and Virtues

Erikson’s theory revolves around stages, conflicts, and virtues. The resolution of these conflicts leads to the development of virtues that serve as strengths throughout life. Below is a table of Erikson’s stages, the conflicts, and the resulting virtues:

Infancy (0-1)

- Conflict: Trust vs Mistrust

- Virtue: Hope

Early Childhood (1-3)

- Conflict: Autonomy vs Shame/Doubt

- Virtue: Will

Play Age (3-6)

- Conflict: Initiative vs Guilt

- Virtue: Purpose

School Age (7-11)

- Conflict: Industry vs Inferiority

- Virtue: Competence

Adolescence (12-18)

- Conflict: Identity vs Confusion

- Virtue: Fidelity

Early Adulthood (19-29)

- Conflict: Intimacy vs Isolation

- Virtue: Love

Middle Adulthood (30-64)

- Conflict: Generativity vs Stagnation

- Virtue: Care

Old Age (65+)

- Conflict: Integrity vs Despair

- Virtue: Wisdom

Erik Erikson’s psychosocial development theory is an essential framework for understanding how children navigate stages of growth. For neurodiverse children. Milestones such as trust, competence, or autonomy don’t always follow a neat, linear path for every child. For instance, children with autism may develop autonomy and competence in different ways, but they can still achieve these milestones. This is where AAC tools become invaluable. They provide alternative communication methods that allow children to express themselves in ways that are meaningful to them, ensuring that their developmental journey is accessible and inclusive.

Rather than seeing child development as a series of isolated stages or conflicts to be resolved, I believe it’s more helpful to acknowledge, identify, and address them as part of who we are at any given point in time. The goal is not to reach the highest stage of development for all. Personally, I value moments of isolation, as they provide space for reflection and self-awareness. Recognition of our capacity for conflict, resolution, and virtue is circular or even spiky, is my personal key to self-acceptance and self-actualisation.

Child Development Evolution timeline

Era: Pre-Industrial Era (Before 1700s)

- Biological: Children were viewed as miniature adults, with no clear distinction for childhood.

- Psychological: Emotional and cognitive development were overlooked; children worked from an early age.

- Social/Societal: Family was central, education was minimal, mostly religious.

- Key Philosophers & Thinkers: John Locke: “Blank Slate” theory (Tabula Rasa); Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Advocated for natural development, childhood as a time of freedom.

Era: Industrial Revolution (Late 1700s – 1800s)

- Biological: Urbanisation led to public health advancements but increased exposure to illness.

- Psychological: Darwin’s evolutionary theory reshaped understanding of human development.

- Social/Societal: Progressive education emerged, with Dewey promoting experiential learning. Froebel introduced kindergarten. Child labour laws emerged; schooling systems expanded beyond religious institutions.

- Key Philosophers & Thinkers: Charles Darwin: Theory of Evolution and Natural Selection; John Dewey: Progressive education and experiential learning; Friedrich Froebel: Founder of kindergarten, play as essential to development.

Era: Early 20th Century (1900s – 1950s)

- Biological: Medical advances improved child health.

- Psychological: Freud and Piaget revolutionised early childhood understanding. Freud’s psychoanalysis and Piaget’s cognitive stages shaped modern developmental psychology.

- Social/Societal: Increased focus on early childhood education, with psychological theories influencing schooling.

- Key Philosophers & Thinkers: Jean Piaget: Stages of cognitive development; Lev Vygotsky: Social-cultural theory, Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD).

Era: Late 20th Century (1960s – 1990s)

- Biological: Advances in neuroscience and genetics led to recognition of developmental disorders.

- Psychological: Erikson’s psychosocial stages highlighted identity and emotional growth.

- Social/Societal: Focus on mental health, identity, and inclusion in educational settings.

- Key Philosophers & Thinkers: Erik Erikson: Psychosocial stages of development; Jerome Bruner: Scaffolding, the role of social context in learning.

Era: 21st Century (2000s – Present)

- Biological: Neuroplasticity and neurodiversity shape modern approaches to child development. Advances in medicine means those with Profound, Multiple and/or Complex Learning Disabilities are thriving beyond previous expectations.

- Psychological: Emotional intelligence, as defined by Goleman, becomes a key developmental focus.

- Social/Societal: AAC tools and inclusive education policies ensure developmental equity for all children.

- Key Philosophers & Thinkers: Daniel Goleman: Emotional intelligence; Norman Doidge: Neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to adapt; Stephen Hawking: Advocate for neurodiversity and inclusion.

Generation Overview, Impact and Mental Health

The generational shifts highlighted illustrate how the understanding of mental health, diagnoses, and special educational needs has transformed over the past century. This progression demonstrates how societal forces like economic conditions, media exposure, and technological advancements intersect to shape how we view children’s growth, behaviour, and emotional well-being.

The Role of AAC in Supporting Child Development

AAC tools as a tool for connection and inclusion enable us to go beyond teaching children to communicate more effectively. We are empowering them to navigate the world with empathy, understanding, and a deep sense of their own value. This aligns perfectly with Maslow’s view that self-actualisation comes not from achieving a singular, predefined goal, but from the freedom to express who we are and connect meaningfully with others.

AAC tools, whether they are high tech, low tech or no tech, are not just about learning or meeting educational requirements; they are tools for connection, transcending the national curriculum to create more meaningful relationships.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: Facilitating Self-Actualisation

Maslow believed that once our basic physiological and psychological needs—such as food, safety, belonging, and esteem—are met, we can then move toward fulfilling our fullest potential, which is self-actualisation.

For children with communication challenges, AAC tools serve as a bridge between meeting these foundational needs and realising their fullest potential. The ability to communicate freely and connect with others is crucial to fulfilling the need for belonging, which is the foundation of Maslow’s theory.

AAC doesn’t just facilitate communication; it promotes a different style of learning—one that places empathy at the forefront.

Chemical Exposure and Sustainability

In parallel with the rise of diagnoses and special educational needs, there has been growing concern about the impact of modern diets and chemical processes on mental health. The mass production of food, with an emphasis on processed ingredients, artificial additives, and high levels of sugar, has been linked to various developmental and mental health issues in children.

Increased exposure to chemicals such as plastics, pesticides, and artificial additives in food production has raised concerns about their effects on children’s neurological and cognitive development. Some studies suggest that exposure to these chemicals can lead to developmental delays, attention issues, and increased vulnerability to mental health conditions like anxiety and depression.

The increasing focus on mental health and special educational needs has led to significant changes in how children are supported in educational systems. Special education provisions have expanded greatly, with a growing understanding that children with neurodiverse conditions such as autism, ADHD, and dyslexia are not “broken,” but rather have different ways of experiencing and interacting with the world.

As we shift towards a more eco-conscious and sustainable future, the question becomes: how do we foster a world that nurtures children’s development in all aspects—biologically, emotionally, socially, and environmentally? As we address sustainability, it’s not just about saving resources or reducing waste—it’s about creating a world where children’s neurodiverse needs are understood, supported, and respected.

Call to Action

I’d love to hear your thoughts! Please share your experiences or reflections on how child development has changed across generations. How do you think these shifts will impact the next generation?

Reflecting on my own parenting journey and considering the influence of mass media and societal tools like parenting guides and Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC), it is clear how these tools and philosophies shape not only how we guide children but also how we understand their uniqueness in relation to their environment.

I think key to it all is the realisation that we all experience these virtues differently, depending on our position, stance, and outlook. This has a profound impact on how we understand neurodiversity and teach children. We are a product of a society that has imposed specific ideas, but we are also part of a society that challenges them.