When Labels Become a Societal and Personal Identity: The Impact of Psychosis and the Schizophrenia Spectrum

Severe psychosis is a complex and multifaceted condition that has long been misunderstood. This post collates expert opinions from Professor Robin Murray, Dr Soumattra Datta, and Associate Professor Keri Ka Ye-Yee Wong, to offer a deeper understanding of the schizophrenia spectrum and neurodiversity.

In his podcast for The Mental Elf, ahead of his keynote talk, Professor Sir Robin Murray reflects on his 50 years of experience as a psychiatrist and researcher. A key takeaway from his reflections is his challenge to the validity and existence of schizophrenia as a diagnostic label.

For decades, the diagnosis of schizophrenia has carried a heavy stigma, akin to other such deficient, permanent, and debilitating labels—both in society and within the medical community. A diagnosis of schizophrenia often meant a lifetime of institutionalisation or heavy reliance on medication, with little hope for recovery.

Given my current knowledge, I was alarmed by the idea of youth diagnosis. In a 12-minute video, Dr Soumattra Datta discusses the misdiagnosis of psychosis in adolescents. He explains the transient and differential understanding of managing psychosis in this population. Dr Datta refers to this as ARMS (At Risk Mental State) and suggests preventative and follow-up measures, along with the dangers of misdiagnosing. In fact, the prevalence rate of schizophrenia in children is only 1 in 10,000, so care must be taken when applying such labels. Additionally, he mentions that neurotypical children can have hallucinations too, often as part of an overactive imagination or transient experiences.

The Spectrum Concept

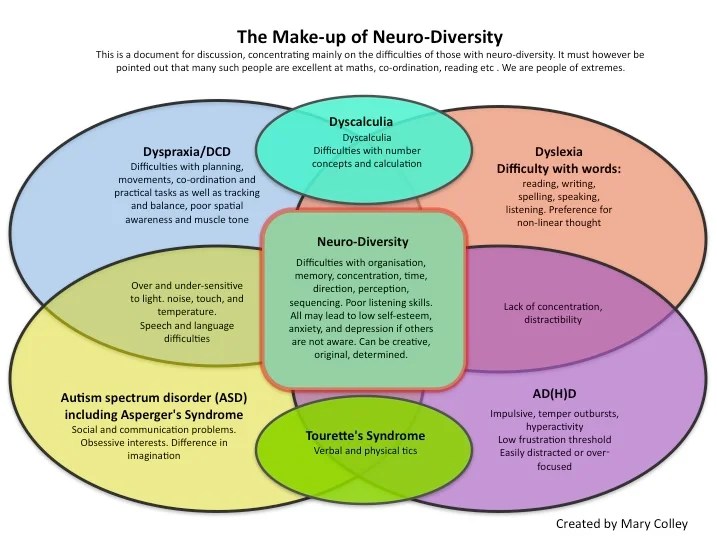

The concept of “spectrum” in mental health disorders, such as schizophrenia spectrum disorders, refers to a range of conditions that share common symptoms or characteristics but can vary in severity, presentation, and impact on daily functioning.

Keri Ka Ye-Yee Wong discusses the core symptoms of schizophrenia spectrum, how they can present, and how these symptoms will vary across individuals. The key takeaway is for families to explore symptoms and ask: Are the delusional beliefs held with conviction? When provided with an alternative explanation, does the child change their mind? Are the hallucinations intense, frequent, or impairing the child’s daily functioning? Have the symptoms persisted for more than 6 months?

Core Symptoms:

- Delusions: Fixed, false beliefs, such as persecutory (feeling others are out to get them), referential (believing ordinary events hold special meaning), somatic (believing something is wrong with their body), or grandiose (having beliefs in special powers or missions).

- Hallucinations: Perceptions of things that aren’t present, such as hearing voices, seeing things (e.g., ants crawling on the skin), or smelling non-existent odors. Heightened sensory perception can sometimes blur the line between real experiences and hallucinations.

- Disorganized Thinking: This may manifest as jumping to conclusions or incoherent speech, making it difficult to follow a conversation or thought process.

- Abnormal Motor Behaviors: This can range from hyperactivity to being mute, showing a lack of movement or response.

- Negative Symptoms: These include a reduced range of emotions (blunted affect), poor eye contact, and social withdrawal.

The Impact of Diagnosis: The Dangers of Labelling and the Evolution of Psychiatric Understanding

Sir Murray advocates for a more nuanced understanding of severe psychosis. He encourages clinicians and the public to recognise that psychosis exists on a continuum, with varying degrees of severity and a range of potential causes. He emphasises that psychosis is not a static condition; it can change over time, influenced by treatment, environment, and individual factors.

He discusses the damage of prematurely diagnosing a permanent, degenerative condition. This can lead to hopelessness for those affected and their families. Professor Murray’s work over the past 50 years demonstrates the evolution of psychiatric thinking.

The Role of Neurobiology in Psychosis: Brain Changes and the Impact of Medication

A central aspect of Professor Murray’s work is his exploration of the neurobiological underpinnings of psychosis. Regarding the evidence of brain changes in people diagnosed with schizophrenia, he suggests that these changes are not necessarily indicative of a progressive, degenerative disorder. Traditionally, the brain changes seen in schizophrenia include a reduction in cortical volume and an increase in fluid-filled spaces, known as ventricular enlargement. These changes have been interpreted as evidence of a deteriorating condition. However, Professor Murray challenges this interpretation. He suggests that these brain changes may not be caused solely by the illness itself. Other factors, such as the effects of long-term medication, could contribute. Antipsychotic drugs, commonly prescribed to manage symptoms of psychosis, are known to have neurological side effects. Some studies have shown that antipsychotics can cause structural changes in the brain, which may be misinterpreted as signs of the condition itself rather than a side effect of treatment.

In addition to medication, lifestyle factors such as smoking, poor diet, obesity, lack of exercise, and high blood pressure all contribute to brain changes that can exacerbate the symptoms of psychosis. Professor Murray’s work highlights the importance of taking a holistic approach to managing psychosis—one that addresses not only the biological aspects of the condition but also the social, environmental, and lifestyle factors that play a role in its onset and progression.

Can Severe Psychosis Be Managed Without Medication?

While recognising that medication can be useful for some individuals, I strongly believe that it should not be the first or only line of treatment for any type of psychosis. As someone who currently relies on antidepressant and ADHD medication, I also know the dangers of over-reliance or the use of something not targeted to the problem.

When medication is prescribed without any other holistic intervention, there is a danger of an over-reliance on medication to address mental health, often overlooking the potential for recovery through non-pharmacological treatments.

Early intervention, psychosocial support, and therapies such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), Cognitive Remediation Therapy (CRT), and family therapy have been shown to be effective in reducing the severity of psychosis and helping individuals manage their symptoms.

Professor Murray advocates for a shift in focus from simply managing symptoms to addressing the root causes of psychosis. For example, he highlights the role of social isolation, drug abuse (particularly cannabis and cocaine), and childhood trauma as key contributors to the onset of psychotic episodes. By addressing these underlying factors, rather than just medicating the symptoms, individuals can experience a more meaningful recovery.

Reducing the Impact of Psychosis: Neurological Acceptance and Holistic Care

Accepting that neurological differences, such as those seen in psychotic disorders, should not be viewed solely through a pathologising lens and understanding that brain changes may be part of a person’s neurodevelopmental makeup, rather than a sign of irreversible disease, can lead to a more compassionate and less fear-driven approach to care.

In addition to medication, Professor Murray advocates for a range of interventions, including psychoeducation, lifestyle modifications, social support, and psychotherapy. By offering a broader spectrum of treatments, we can better support individuals experiencing severe psychosis, while also reducing the stigma and fear associated with psychological challenges.

Conclusion: The Importance of Rethinking Labels

The work of Professor Sir Robin Murray represents a pivotal shift in our understanding of severe psychosis. His research highlights the complexity of psychotic experiences, urging us to move beyond simplistic labels like schizophrenia and recognise psychosis as part of a spectrum of mental health conditions that can be managed with a variety of treatments.

Professor Murray does not focus solely on medication or accept a grim prognosis. Instead, he advocates for a more compassionate, holistic approach to care. This approach addresses not only the biological factors but also the psychological, social, and environmental influences that shape mental health.

The work of professionals like Professor Murray serves as a reminder that severe psychosis is not an inevitable degenerative disorder. It can be understood, managed, and even mitigated through a more nuanced understanding of the condition. A more personalised approach to treatment is essential for meaningful recovery and improved outcomes.

For further insights on managing schizophrenia spectrum disorders in children and adolescents, please visit Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders in Early Childhood, Management of Psychosis in children and Adolescents and The Mental Elf Podcast.

Local links

Psychotherapist Mamta Bajaj is a psychotherapist, clinical trauma counsellor, and CBT therapist based in Bangkok. She runs a non-profit organisation in Thailand that facilitates discussions on gender-based and sexual violence trauma.

Access her Anxiety Mantras and techniques for managing intrusive thoughts at Three Point Counselling.

Additionally, she offers a free 20-minute counselling session for well-being, alongside CBT, ERP, Humanistic, Somatic, and Mindfulness therapies that align with the messages in this post, based on my own experience and thoughts on how best to support families facing crisis.