I had the pleasure of joining Dr. Donna at the British Club today for her fascinating talk. She covered a range of crucial topics. This included the current ageing and low birth rates in Thailand. She also discussed occupational health and depression. Additionally, she talked about COVID-19 and the rise of new treatments like Ozempic.

One of the most significant points she made was the role of healthcare professionals in listening. It’s essential to speak the same language as patients, and this is not simply a linguistic issue. Truly hearing their struggles is crucial. Understanding their journey is equally important, whether it’s a health challenge or a mental block.

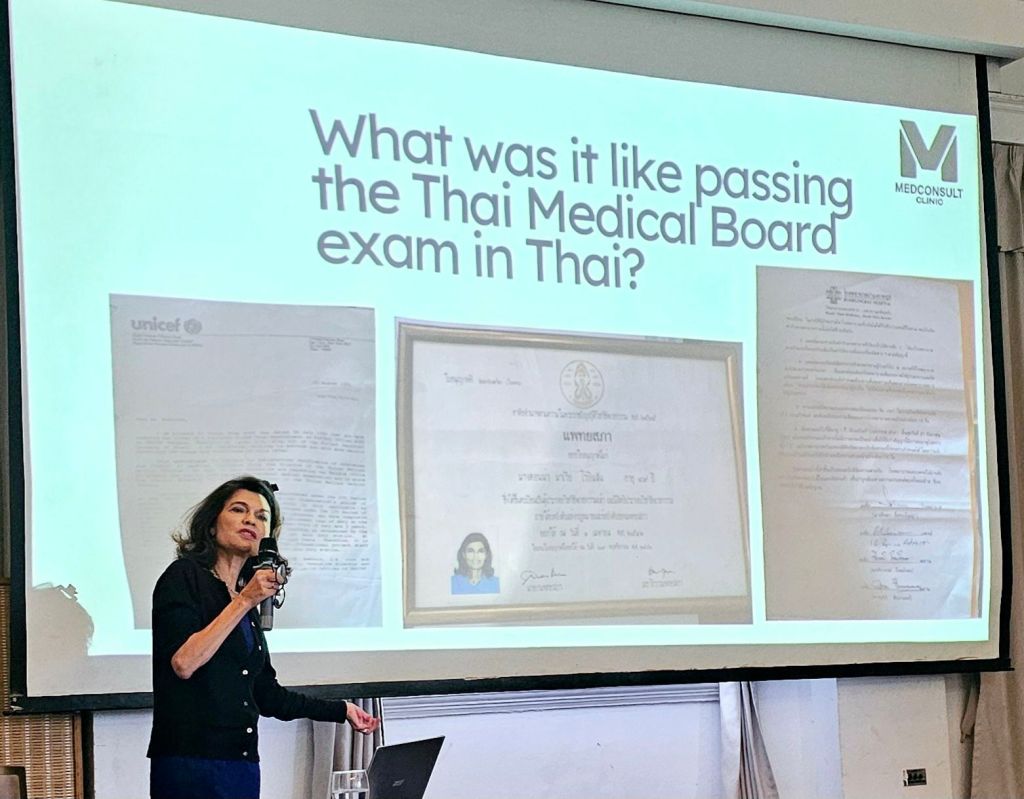

Dr. Donna’s story

Dr. Donna’s story is quite remarkable. Her career and qualifications are impressive, and the way she sought to address the needs of an expatriate community in Thailand is commendable. It’s clear that her decision to study for the Thai medical exam and open her own clinic was driven by a genuine desire to help others. Her approach to meeting the specific needs of newcomers to the country reflects a thoughtful and purposeful career path. It’s certainly a story worth hearing.

Evolving medicine, treatments and definitions

Dr. Donna reflected on how opinions and practices that were once widely accepted are now evolving. She noted how people’s opinions, knowledge and needs shift, and that the terminology surrounding these needs is also changing. Our collective views have changed significantly. This is true in many areas, including ethnicity, marriage, ageing, and healthcare definitions. It also applies to issues surrounding modern medicine and treatments. This change speaks to the broader discussion of healthcare advancements and the challenges they impose on a country’s economy.

The discussion about the word geriatric led me to think about the evolving terminology surrounding special needs. The term “geriatric” was once used to classify someone as elderly at age 60. Later, that age was stretched to 70, and then no longer used. Similarly, the term sub-human was used many years ago to classify people with disabilities, particularly intellectual disabilities. Disabled has become special educational needs and disabilities (SEN or SEND). The dilemma around terminology is significant. How can we describe important characteristics without causing offense? How can we avoid creating poor self-regard? This is especially important considering a growing population of adolescents with disorders. We need to understand and address their needs, especially from a cultural perspective. Personally, I believe the description should at least, not include a deficit label.

Medical advancement and longer lives

The parallel between the ageing population and the special needs community and effect is also notable. Advances in healthcare allow children and adults, who might not have survived in the past, to live longer now. This population includes those with Profound Intellectual Learning Disabilities also described as people with Complex Learning Disabilities and Profound and Multiple Learning Disabilities/Differences. Much like the increasing ageing population, this group requires more medical professionals specialising in their care. Similar challenges arise in the availability of trained providers.

Equality and values

The topic of human inequality is also relevant. In the history of medicine, if a doctor inadvertently caused the death of a patient, they would be sentenced to death. However, if the person was a slave, the doctor was not punished in the same way. The doctor would simply be ordered to replace the worker. During the COVID-19 pandemic, a Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) order was issued for individuals classified as PMLD (Profound and Multiple Learning Disabilities). This raised questions about the societal value of their lives.

Cosmetic Pharmacology

Conversations with Dr. Donna are always interesting, and today’s meeting sparked thoughts about cosmetic pharmacology. This term refers to people self-administering substances like stimulants or relaxants without medical oversight. For example, some people use methylphenidate, a stimulant, to improve concentration. The moral question here lies in the danger of unregulated drugs—whether they’re used for beauty, cognitive enhancement, or anything else. The risks are real, and without professional guidance, there could be disastrous consequences. This is also similar to the lack of regulation in non-invasive beauty services, where improper oversight can lead to complications.

Stigma, holistic care and self-determination

The stigma surrounding issues like mental health, labelling, and cosmetic enhancement procedures can be overwhelming. I have found that people may feel reticent to share their experiences. Mental health issues and seeking support to focus or look and feel better are not things to be ashamed of. In fact, these decisions can have a profound, positive impact on one’s self-esteem and overall well-being.

There’s often an underlying pressure to conform to certain ideals, which can lead to feelings of shame or embarrassment. Cosmetic pharmacology, when approached responsibly, can enhance potential. It can also aid in self-actualisation and personal growth when done under the care of a medical professional. Dr. Donna highlighted a key point: people need support in complex situations. This is especially true when they struggle mentally to make changes themselves. People should be empowered to make choices that help them feel their best, without fear of judgement.

Compassion and care

Dr. Donna’s work is undoubtedly a privilege to be a part of and a testament to what compassionate, well-rounded healthcare can look like.

As someone who’s lived in Thailand for a while, I’m particularly grateful for Dr. Donna’s practice, which offers a rare combination of beauty care and medical services under one roof. Her holistic approach to healthcare resonates with those of us familiar with a more integrated system. This community-based system is common back home in the UK. Her model offers a blend of accessibility and support. It includes online consultations and home visits for those unable to visit the clinic in person.

For me, her clinic is a practice that truly puts the patient’s needs first. This approach is all too often overlooked in modern, private healthcare systems.

Societies shape systems

These issues impact how societies shape systems. They reflect not only medical advancements but also evolving social and cultural understandings. We are increasingly aware of the value of all people, and neurodiversity, whether they are disabled, brilliant, or otherwise. The inclusion and visibility of people and families with disabilities is particularly close to my heart. Each person helps shape the world we live in. They also influence the future of healthcare and humanity.

Knowing Dr. Donna is truly a privilege. Her support as a healthcare provider is inspirational and empowering.

References:

Aging and Low Birth Rates in Thailand:

World Bank, UN Population Division.

Thailand’s fertility rate has decreased in recent decades, which raises concerns about the country’s ageing population.

Ozempic:

NHS Choices, British Medical Journal (BMJ).

Ozempic (semaglutide) is prescribed for diabetes but is also used for weight loss.

Listening in Healthcare:

NHS Leadership Academy, British Medical Association (BMA).

The importance of effective communication and listening in healthcare to improve patient care.

Geriatric Terminology:

British Geriatrics Society, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

The changing definition of geriatric in medical contexts and age classifications.

Historical Use of “Sub-human”:

Disability History Scotland, UK Disability History Archive.

The use of dehumanising terminology to classify people with disabilities in history.

Use of the Term “Disabled”:

Disability Rights UK, Scope.

The evolving terminology from “disabled” to “special educational needs” and related terms.

Profound Intellectual and Multiple Learning Disabilities (PMLD):

NHS Learning Disabilities, National Development Team for Inclusion (NDTi).

Terminology and care for individuals with profound intellectual and multiple learning disabilities.

Medical Inequality and Historical Punishments:

History of Medicine, Journal of Medical Ethics.

Historical examples of doctors facing different consequences depending on their patient’s status.

COVID-19 and PMLD DNR Orders:

BBC News, Disability Rights UK.

The ethical controversy over Do Not Resuscitate orders for individuals with disabilities during the pandemic.

Cosmetic Pharmacology:

British Journal of Psychiatry, UK Drug Policy.

The rise of self-administered substances for cognitive enhancement and beauty purposes.

Regulation of Non-Invasive Beauty Services:

British Association of Dermatologists, Health and Safety Executive (HSE).

Regulation gaps in non-invasive beauty treatments and their health risks.

Holistic Support in Healthcare:

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), The Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP).

The rise of holistic care and integrated services in healthcare settings.

Glossary of Terminology

- Geriatric:

Traditionally used to describe elderly individuals, the term geriatric has been evolving in medical contexts, and is now being replaced with more inclusive language. - Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEN, SEND):

This term refers to students who have difficulties learning in comparison to others of the same age. It encompasses a wide range of conditions, from mild to profound, and includes conditions like autism, dyslexia, and learning disabilities. - Profound Intellectual and Multiple Learning Disabilities (PMLD):

Refers to individuals who experience severe intellectual and developmental impairments. People with PMLD typically have complex health and care needs. They may require assistance with most aspects of daily life. This includes communication, mobility, and personal care. - Complex Learning Disabilities:

Children and young people with complex learning difficulties and disabilities (CLDD) include those with co-existing conditions (e.g. autism and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), multisensory impairment, Social Emotional Mental Health issues (SEMH)) or profound and multiple learning disabilities (PMLD). - Cosmetic Pharmacology:

A term that refers to the use of substances, that are self-administered without medical oversight, and are often used for cognitive enhancement or cosmetic purposes, such as weight loss. - Ozempic:

A medication that contains semaglutide and is primarily used to manage type 2 diabetes. However, it has recently gained attention as a treatment for weight loss. This has raised ethical questions regarding its use for non-diabetic patients, and it also raises medical questions for those not classified as obese seeking cosmetic enhancement. - Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) Orders:

A medical order to not initiate CPR or other resuscitation measures if a patient stops breathing or their heart stops beating. These orders are sometimes applied to patients with PMLD. This has raised significant ethical questions about the value and rights of individuals with disabilities. - Mental Health Stigma:

Social stigma surrounds mental health issues. This can result in individuals being judged, excluded, or discriminated against. This stigma can affect people’s willingness to seek help. It also influences how they are treated by others, particularly in the context of healthcare. - Medical Inequality:

Refers to the disparities that exist in healthcare, based on factors like race, class, gender, disability, and other social determinants. Historical examples demonstrate the devaluation of certain groups in medical practices. Slaves or individuals with disabilities are examples. - Holistic Support:

An approach to healthcare that focuses on treating the whole person, not just the illness or symptoms. This involves considering physical, emotional, social, and mental well-being. Care should address these multiple aspects of a person’s health. - Non-Invasive Beauty Treatments:

Refers to aesthetic procedures that do not require surgery or significant medical intervention. Examples include botox, dermal fillers, and laser treatments. Despite being minimally invasive, these procedures can still pose health risks when not properly regulated. - Profound Intellectual Learning Disabilities (PILD):

This term may refer to individuals with deep cognitive and developmental impairments. It is similar to PMLD. However, it can encompass a broader category of intellectual disabilities, focusing on those with more profound challenges.