Beliefs shape how we see the world.

Belonging shapes how we survive in it.

And if we can’t always answer how, maybe we go back to why.

Today I attended a business workshop where we discussed passion, burnout, and bouncing back. It helped me connect some of the things that have been quietly sitting in my brain for a while: beliefs, belonging, burnout – and what comes next.

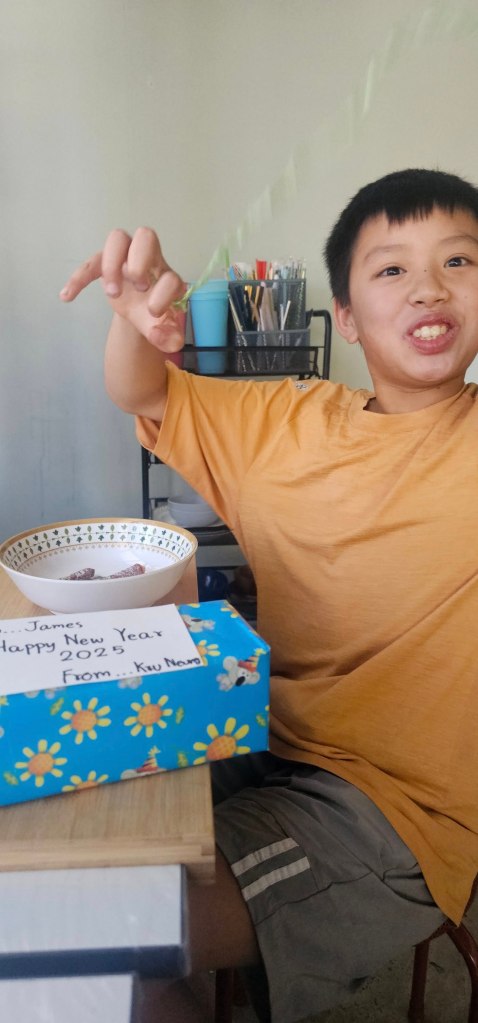

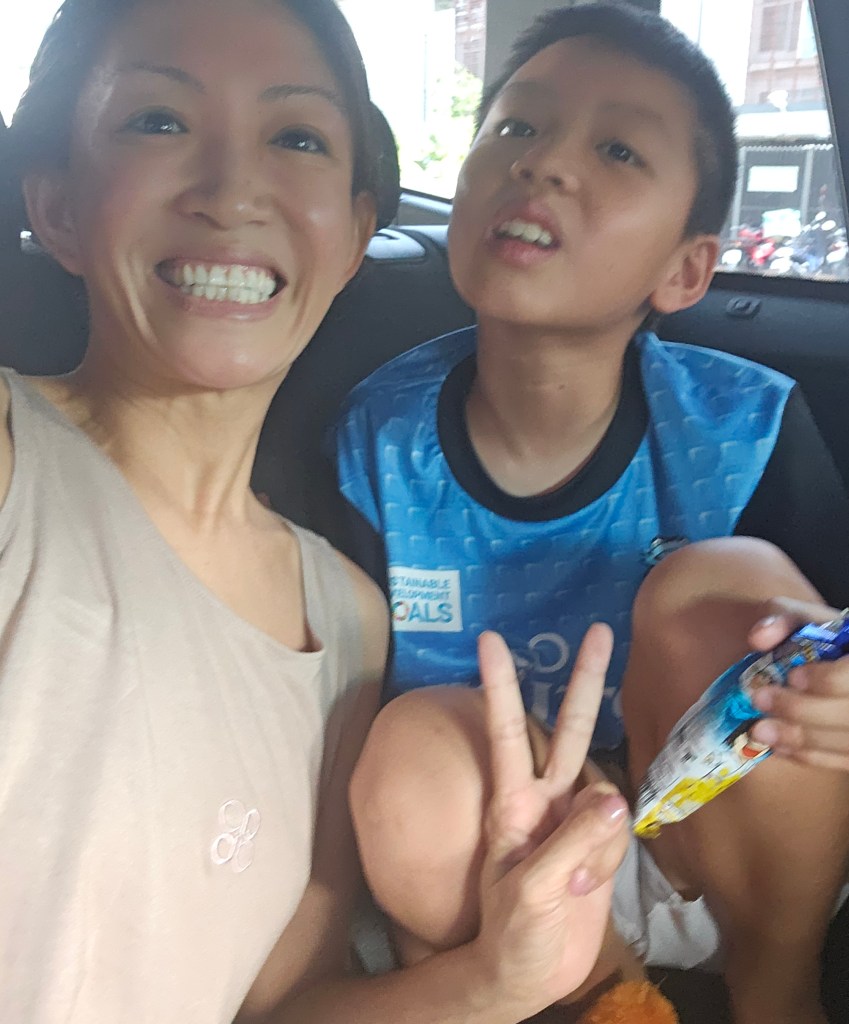

But let me backtrack. A new stim appeared today. I found myself wondering—was James trying to show something he couldn’t yet say? These are the kinds of questions I ask myself often. I overthink. But sometimes, that overthinking helps me notice patterns, to piece together signals that might otherwise go unseen. That brings me back to beliefs and burnout. I burn out because the load is heavy—juggling life, learning, teaching, and creating tools. Even things I love can weigh me down when there’s no room to pause.

Lately, I’ve been experimenting with AI tools—training image generators to create meaningful visuals for my projects. I hoped it would make things easier. The results are inconsistent: brilliant one moment, bizarre the next. In a way, it reminds me of autism and the term spiky profile. Like that term, these tools can be great in one area and miss the mark in another.

It also reflects something deeper: expectations.

We often expect people—especially children with additional needs—to “perform” to certain standards. We do this without pausing to understand the gaps in comprehension, communication, or cultural background.

Take a sandwich, for example.

If you give someone butter, bread, chicken, and egg, what do they make? That depends on where and how they were raised. Do they toast it? Does the butter go inside or outside? What goes first—the chicken or the egg? How would an untrained Artificial Intelligence Bot make it? (Ha.)

The point is: the “rules” are cultural. Learned. Assumed. Alien to some! Yet sometimes, experimenting outside those rules leads to something beautifully unexpected.

If the response is supportive—“that’s a creative idea,” or “tell me more”—it becomes part of a learning process. But if the response is “not like that” or “that’s wrong,” it can feel alienating. This can erode confidence. Imagine the frustration. Imagine facing that type of reaction with almost everything, all the time.

The challenge deepens when rules change depending on where you are too. I navigate language and systems in a culture that isn’t my own. My lifestyle doesn’t always fit the norm. The strain of not quite fitting in is something I feel often. This is especially true in this international world. Many of us are raising third-culture or even fourth-culture children. The layers add up. Different languages, different social cues, different systems. It’s no wonder burnout is common. Burnout isn’t just tiredness. It’s a state of mental, emotional, and physical depletion. It’s the slow erosion that comes from constantly adjusting to expectations that weren’t designed with you in mind. I see it in my child. I feel it in myself. And I read about it in parent communities.

I do overthink. I do burn out. But to counteract the signals, I’ve built myself a first-aid kit for those moments. I exercise, listen to music, read, sing, or work. I remind myself it’s okay to not be okay. It’s not perfect, but it helps. Sometimes I still hide. Tomorrow might be the day I’m a little less afraid.

Maybe the answer is simple: We are human. We evolve. We are the species that invented aircraft and landed on the moon. We can make life better for those living with depression or anxiety, or those who feel like they don’t belong. We can build systems of communication that meet people where they are. We can create roles and spaces that value what people bring, not just measure what they lack. People have the power to make meaningful change.

I write to make sense of it all—for myself, and for James. To find a way move beyond his current way of communicating.

For every child and parent who feels like they’re getting the sandwich sign wrong, but keeps trying anyway.

And maybe, through it all, we can create a space for hope, answers, belonging, and a little magic. Maybe tomorrow that stim will have gone away. TBC 🙂