In a nutshell, AAC, or Augmentative and Alternative Communication, refers to methods used by individuals who struggle with speaking or writing to express their thoughts, needs, and ideas. AAC doesn’t just facilitate communication; it promotes a different style of learning—one that places empathy at the forefront.

- No-Tech, Low-Tech, High-Tech approaches

- How can AAC aid learning for those with minor learning challenges?

- Why would speaking people use it?

No-Tech, Low-Tech, High-Tech approaches

Low-tech AAC includes simple tools like pictures, visuals, or printed symbols. For example, a person might use a picture board with images of everyday items to communicate needs or wants. It can also include using a computer or camera to create or show visuals to aid communication. Low-tech solutions are accessible and easy to implement in various settings, offering an effective way to support communication without needing advanced technology.

No-tech AAC could be using everyday objects as symbols or objects of reference and body language. For instance, an individual might use the wrapper of a favourite food to signal a desire for that item. Additionally, facial expressions, basic gestures and Makaton (simplified, non grammatical sign language) are all important no-tech communication tools. These methods make use of what we already have at hand to communicate effectively.

High-tech AAC involves more advanced tools like speech-generating devices, applications, vocal output devices, switches or eye-gaze technology. These tools provide individuals with more complex and dynamic ways to communicate, offering them the ability to produce speech, text, or even control their environment. Vocal output devices can be particularly useful for individuals with severe communication impairments, giving them a greater degree of control over their interactions and choices. Equally, sophisticated speech-generating applications support language learning by reinforcing structure, syntax, and semantic coding — helping children build meaningful, grammatically rich communication. Speech-generating applications (SGDs) can support language development by organising vocabulary into categories and grammatical structures, tools to help reinforce sentence building. This structured approach allows children to form more meaningful, age-appropriate communication over time, even when spoken language is limited.

Switches other enabling devices

For individuals with very impaired communication abilities, switches can offer opportunities to make choices and effect change in their lives. Switches are simple, accessible devices that allow users to make a selection or communicate by pressing a button. These can be connected to various devices, enabling a person to activate communication aids or control their environment, such as turning on a light or selecting a recorded message which enables a person to communicate basic needs or responses, such as saying “I want a drink” or “I need help,” with just one press of a button. These tools provide an invaluable opportunity for individuals who cannot use more complex speech-generating devices to still exercise choice and have a say in their daily lives.

Nowadays, there are inexpensive toys that allow you to record simple messages so this idea can be adapted to suit the individual.

In a nutshell, AAC is all about providing alternative ways for people with speech or language challenges to communicate effectively with others.

How can AAC aid learning for those with minor learning challenges?

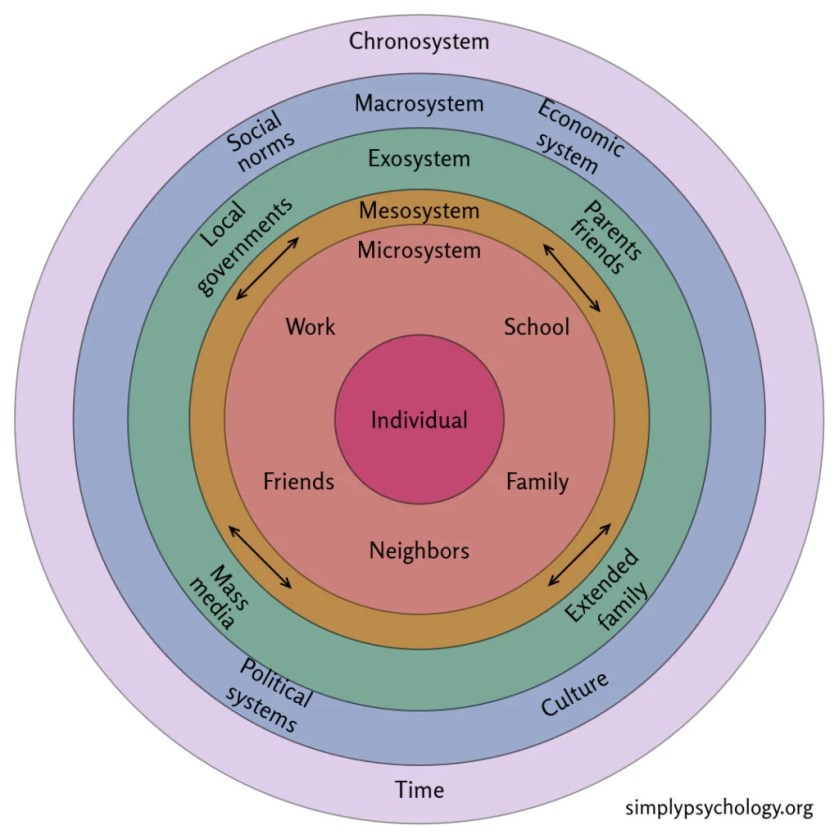

AAC can play an important role in supporting individuals with minor learning challenges by helping them communicate and engage more effectively in their learning environments. Here are some of the ways it aids learning:

- Improved Clarity and Expression: Whether using pictures or speech-generating devices, AAC helps individuals express their thoughts clearly, reducing frustration and promoting greater participation in classroom activities and discussions.

- Support for Reading and Writing: For individuals with challenges such as dyslexia, AAC can assist with reading and writing by offering visual cues, word prediction, and text-to-speech options. These tools make it easier for students to access and express information.

- Boosting Confidence: Many learners with communication difficulties may feel isolated or unsure of themselves in class. AAC methods, from picture boards to more advanced devices, offer them ways to engage and build confidence in their learning journey.

- Reinforcing Concepts: Visual aids and symbols used in AAC can reinforce learning concepts, helping learners better understand and retain information. These supports can help break down complex ideas and make them more accessible.

- Personalised Learning: AAC can be tailored to suit each individual’s unique needs. Whether using low-tech tools like pictures or high-tech speech-generating devices, AAC makes learning more accessible and ensures that students can engage in ways that suit their abilities.

Why would speaking people use it?

Speaking people might use AAC for several reasons, even if they can talk. Here are some common scenarios:

- Temporary Speech Loss: For individuals recovering from surgery, illness, or injury (e.g., after vocal cord surgery), AAC can help them communicate while their speech returns.

- Speech or Language Disorders: Some people have speech disorders like stuttering or aphasia (a condition that affects speech after brain injury), where AAC can serve as a backup or enhance communication.

- Accessibility: In noisy environments or situations where speaking is difficult (e.g., in a loud crowd or during meetings), AAC devices can offer a clearer way to communicate.

- Enhancing Communication: For some, using AAC can support more efficient communication, especially if they have specific needs or prefer to use visuals or text.

- Multilingual Communication: AAC tools may be used to bridge language barriers between people who speak different languages.

In these cases, AAC can act as a useful tool to improve communication, clarity, and accessibility, even for people who are able to speak.